Introduction

WHAT IS THIS THING and WHY DOES IT TAKE SO LONG FOR YOU TO UPDATE IT?

The intent of this Handbook is to give a moderately good grounding in the basic principles of sound and theatrical sound design and reinforcement in an easy-to-digest format. There are now a slew of books on sound, sound reinforcement, concert sound, and theatre sound, but I haven't found one that is basic enough for the beginner yet compelling enough for the professional. What I have found are poorly-written selections with too many manufacturer endorsements. But back when I started this book, there weren't that many resources available to you, gentle reader.

I started compiling a sound handbook which described sound systems (basically for the theatre) and how to design them / operate them as a lark a very, very long time ago (okay, I was in high school). It was originally designed to educate fellow tech theatre students in the basics of sound. A few years after that, I rewrote the handbook and posted it on-line (remember NCSA Mosaic? Yup, so do I), transferred servers, and since then there have been sporadic bursts of activity on this website, whenever the mood strikes me or when I am on vacation. Like most writers, I find the impetus to write appears late at night when I am very tired and have nothing better to do, or when I'm extraordinarily bored in some foreign city with no one around. Neither of these situations occurs very frequently. I suppose if I took heroin, this book would have been finished by now, but I don't, so you'll just have to deal with the meandering process of the Sound Handbook.

WHAT IS THEATRICAL SOUND DESIGN?

The term "Sound Design" encompasses many different disciplines. At its most mundane definition, Theatrical Sound Design is the creation and execution of aural stimuli to enhance the mood of a stage work and/or to facilitate the telling of the work.

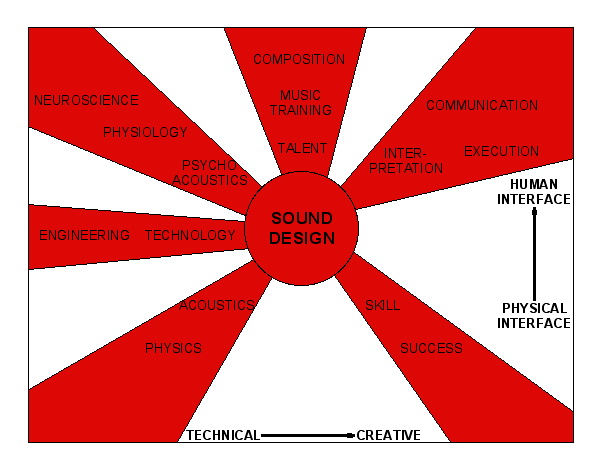

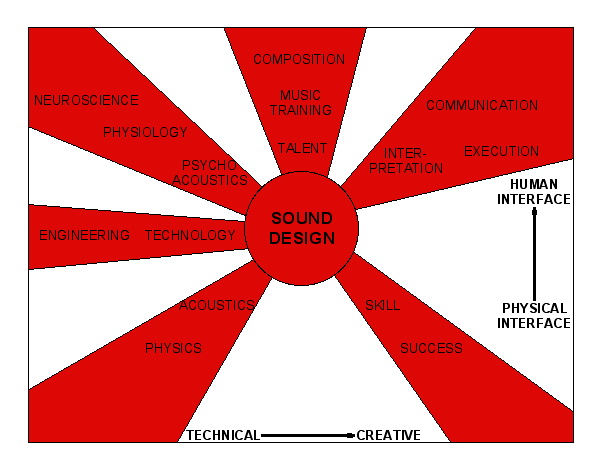

This crudely-drawn illustration, paying homage to half of my homeland, is meant to show the many facets of sound design. The left-hand side of the drawing covers the technical knowledge; as we progress to the right side, we use more of the other side of the brain; the creative side. At the same time, the bottom of the picture illustrates the physical, more quantifiable qualities, while the upper portion of the flag shows the interface with the human being.

In the lower left quadrant, we have our scientific knowledge: acoustics and physics, the study of sound in a physical space, is a vitally important part of sound design. Designers constantly need to work with or around the physical qualities of the venue in which they are working. The study of acoustics begets the study of physics, which helps to explain and quantify acoustical qualities.

In the middle of the left-hand side we have the ambiguous and much overused term technology, by which we mean the tools that are used in the creation and execution of a sound design. Technology begets engineering, the nuts and bolts of the technology; the electromechanical principles necessary for the creation and dissemination of sound, very closely tied to physics, below.

In the upper left quadrant we have our human counterparts: psychoacoustics is the study of how we hear. Why, for instance, do we perceive major scales as more "pleasing" than minor scales? What makes an octave an octave? Further along we are introduced to human physiology and the actual hearing components of our sensory system, followed by neuroscience, the study of brain activity, in this case as it relates to aural stimuli.

At the top we have another ambiguous term: talent, which is influenced by many different factors, most importantly musical training and composition, whether it be musical composition or effect composition, and performance skill— the difference between a well-trained performer and an inexperienced one.

In the upper right quadrant we have our creative/human interface. Interpretation is a highly subjective matter, as everyone hears differently and reacts differently to aural stimuli. Execution is the ability to transmogrify creative ideas into physical results utilizing technology, and the communication is, of course, the ability to interpret creative ideas in a unquantifiable form into a language that can be mutually understood.

WHAT IS A THEATRICAL SOUND DESIGNER, AND WHY DO YOU NEED ONE?

A sound designer needs to be a jack-of-all-trades, capable of speaking in scientific terms when necessary, to communicate with other sound staff or acousticians, but also needs to be capable of interpreting ideas from other members of the creative team, often in a vague and unclear manner (i.e. "I want this to sound more... BLUE!"). The sound designer must recognize what kinds of tools are available for his or her use, and how to use them to effect the desired response, and be able to communicate to technical staff how to use them, while simultaneously being able to discuss issues of creativity, of music, of composition, and of performance. A sound designer is the interface between creativity and technology.

Any half-trained monkey can set up a microphone and a loudspeaker for public address systems or corporate conferences, but a sound designer is much, much more than that. A sound designer takes ideas, based upon a collaborative approach to a musical or dramatic work, and enhances those ideas, either in the form of prerecorded sound effects or by ensuring that all orchestrations, lyrics, and text are clearly heard by all members of the paying public.

Return to the Sound Index. Continue to the Sound Introduction.

Comments, Questions, and Additions should be addressed via e-mail to Kai Harada. Not responsible for typographical errors.

http://www.harada-sound.com/sound/handbook/intro.html - © 2003 Kai Harada. 01.12.2003.

09.08.1995, 27.02.1996, 10.07.1996, 07.11.1999, 12.01.02, 01.12.03.